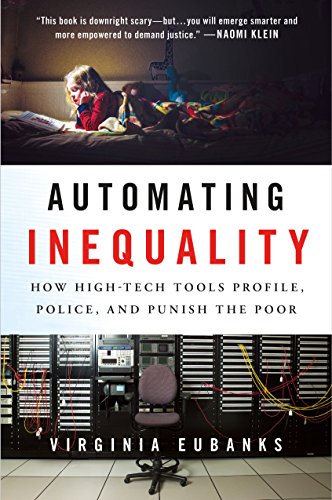

I recently read Automating Inequality by Virginia Eubanks and would like to share some thoughts. This review is the first of several book reviews I’ve been working on about books relating to the problems which are emerging from technology. I’ll keep this brief…

I recently read Automating Inequality by Virginia Eubanks and would like to share some thoughts. This review is the first of several book reviews I’ve been working on about books relating to the problems which are emerging from technology. I’ll keep this brief…

The Good:

I am glad that the conversation about social problems caused by technology is expanding. Books like Automating Inequality are good contributors to that discussion. In this book, Eubanks highlights a few situations where technology has negatively affected people’s lives, primarily poor people. This technology also serves to limit poor people’s lives and opportunities, creating what she refers to as a digital poorhouse.

The use of machine learning can be a powerful tool for developing predictive analytics to One abuse which I found particularly troubling was cited on pg. 137 which is a risk model which calculates a risk score for unborn children.

Vaithinathan’s team developed a predictive model using 132 variables–including length of time on public benefits, past involvement with the child welfare system, mother’s age, whether or not the child was born to a single parent, mental health, and correctional history–to rate the maltreatment risk of children in MSD’s historical data. They found that their algorithm could predict with “fair, approaching good” accuracy whether these children woudl have a “substantiated finding of maltreatment” by the time they turn five.

What I Found Lacking:

What I found lacking in Automating Inequality was the lack of alternative proposals. It is easy to criticize a technical solution, but these systems are often deployed against complex problems and finding a solution often requires a lot of vigilance, persistence and iteration. Eubanks discusses the issue of welfare abuse, and seems to downplay the fact that welfare fraud is in fact a major issue in this country. With some basic research on Google you can unfortunately find countless cases of individuals convicted of welfare fraud. Clearly, welfare programs should make efforts to reduce fraud and make sure that their resources are going to people who truly need the assistance.

What Eubanks seemed to miss was what went wrong in the implementations that she highlighted. In two cases, Eubanks highlighted several systems designed to improve the efficiency and efficacy of welfare programs. From the book, it sounded as if the designers of these programs implemented various technical systems to automate the intake process for benefits. What didn’t happen, and what Eubanks didn’t discuss in the book, was what was missing in these programs: continuous improvement. The government agencies that implemented these programs took the approach that one would take when one is building a bridge or tunnel: get it done and once its done, move on to the next project. This doesn’t work for information systems because they are never done. Once you start using them, there will always be faults and opportunities to improve. If an organization can rapidly iterate and improve the solution over time, they will end up with an effective solution.

Eubanks ends the book with a proposed code of ethics for data scientists and other technologists. I wrote my own code of ethics for data scientists, and it is always interesting to me what others write on the subject. I particularly liked these points from Eubanks’ Code of Ethics

- I will not collect data for data’s sake, nor keep it just because I can

- When informed consent and design convenience come into conflict, informed consent will always prevail. (If only it were so… )

Overall, I found the book to be quite thought provoking, but I did disagree with some of the conclusions.